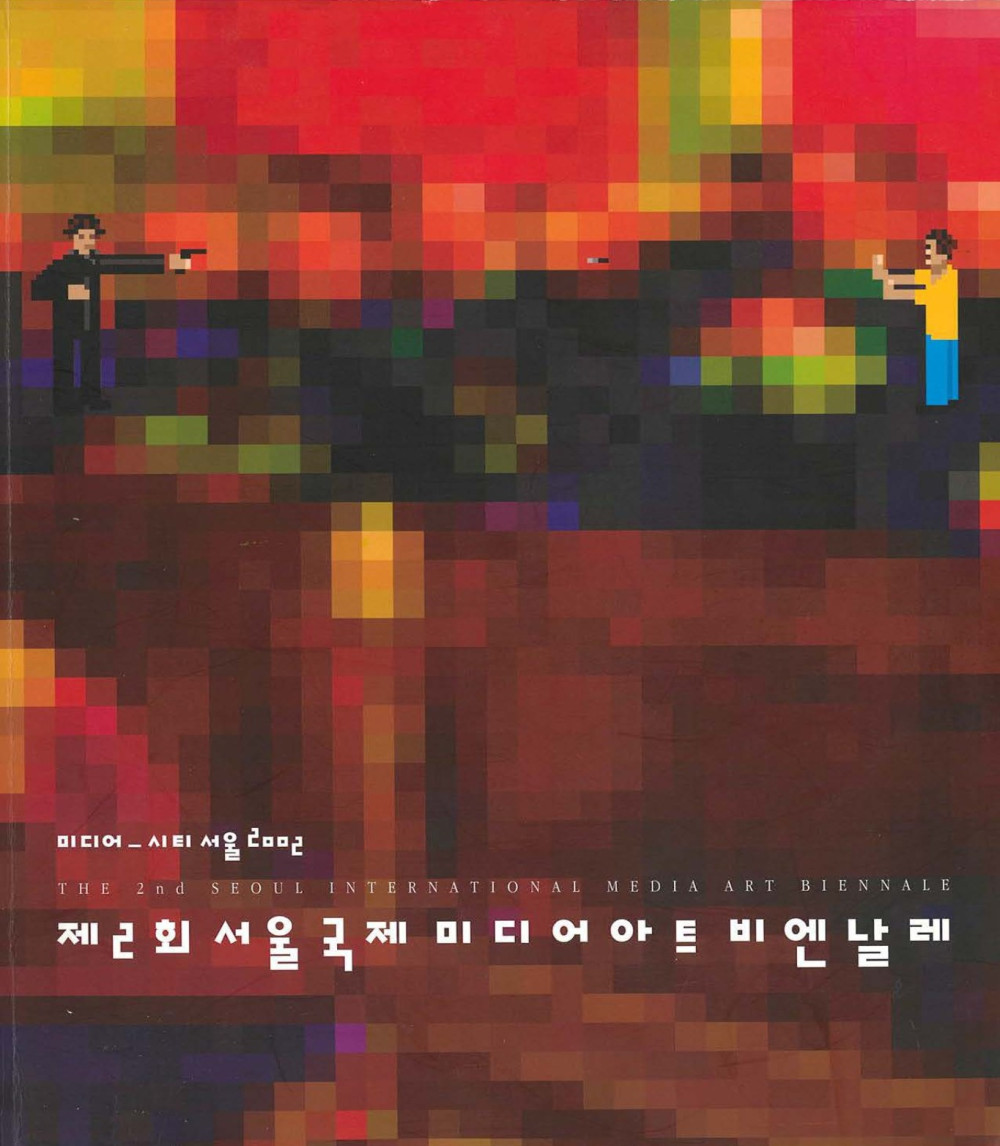

The World as Super Mario sees it: art after videogames.

Looking back at Lara Croft, I realize that Tomb Raider was such a bad taste game. How did I happen to spend so much time in 1997 playing it? I would bring Lara around, in the labyrinths of the game, kill her or save her, let her wait in dark corridors and go to sleep, wake up the next day and just have her look around. I was the girl but also the person who controls the girl and at the same time I was someone who is looking from the outside: a cameraman. Ultimately, I would take hundreds of pictures of her, and from her, from what her eyes would see. They were screen snapshots, which I would print on photographic paper, by using a jet ink printer, then wash the prints in the bathroom while the ink was still wet—in order to apply some extra expressionism. After they would dry, I would send these prints to the photo laboratory, where they would enlarge them using a technique called vibracolor and FedEx them to art shows.

In the beginning, nobody would recognize Lara Croft, because nobody knew about her yet. Collectors would ask me what was the program that I used to draw her, and after I explained that this was a character taken from a videogame and that I changed almost nothing, they would walk away confused. “Is this art?” they would ask their wives or the gallerist. “This guy did nothing after all; anybody can take a picture from a cartoon and print it large.” For that matter, anybody at the time of Goya or Jacques-Louis David could make the portrait of the gentleman, or in earlier times, paint a picture where an Italian lady with a pretty round face keeps in her arms a baby. But if the person on the painting happened to be the King, or Napoleon, and if the lady was a Madonna and the baby a Jesus, then people would look at it differently. How the picture has been manufactured was not so important anymore; what would instead matter was the fact that the artist had introduced in the world a representation of a celebrity and by doing so, he had revealed the essence of that celebrity.

The valuable information which the artist would diffuse with his picture was the fact that the celebrity was a fake, a metaphor, a piece of fiction. The painting would show to anybody who had eyes to see and a brain to acknowledge that the King is just a guy dressed up to be King, Napoleon is a short man who plays Napoleon, and Madonna with her Jesus were just a nice family with a tragic destiny. Nothing and nobody is really what is supposed to be, and the same happens with nature such as a long river, a flat sea landscape, or a red apple. What appears is always a matter of transcription through our perception or it is related to the place that we occupy in the World.

Abstract Super Mario, 1998. performance, DVD player, projector, PDP screen, speaker, sofa. dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist