The work of Rafael Queneditt Morales (1942-2016) was rooted in the African spiritual inheritances of Cuba. Both as an artist and as the founder of Grupo Antillano—a collective of visual artists, intellectuals, writers, and musicians—he promoted an Afro-Cuban culture marginalized by colonial and Communist administrations alike.

In the context of his own work, informed by his study of the history of the Antilles and its cultural links to Africa, this often manifested in the representation of Afro-Cuban deities, mythologies, and ritual practices. In common with many artists in this exhibition, Queneditt Morales’s commitment to spiritual experience in a predominantly secular context would prove an impediment to his career. This was especially the case during the Quinquenio Gris (1971–1976), a period of cultural repression in Cuba characterized by hostility to minority groups, censorship, and the suppression of ideological positions contrary to the Communist orthodoxy.

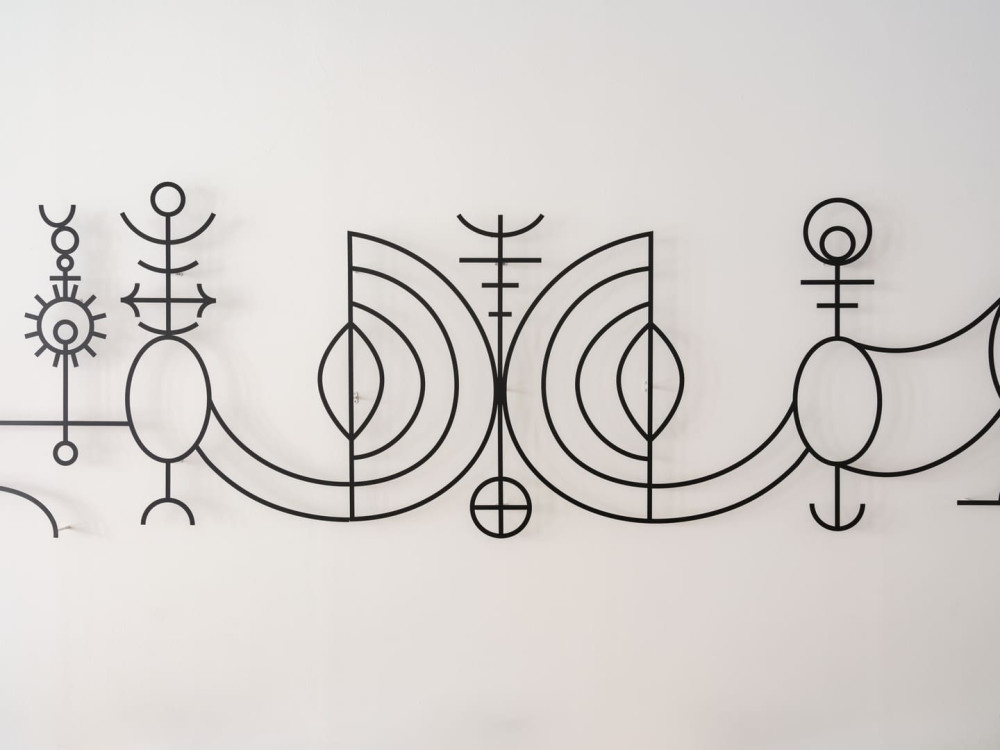

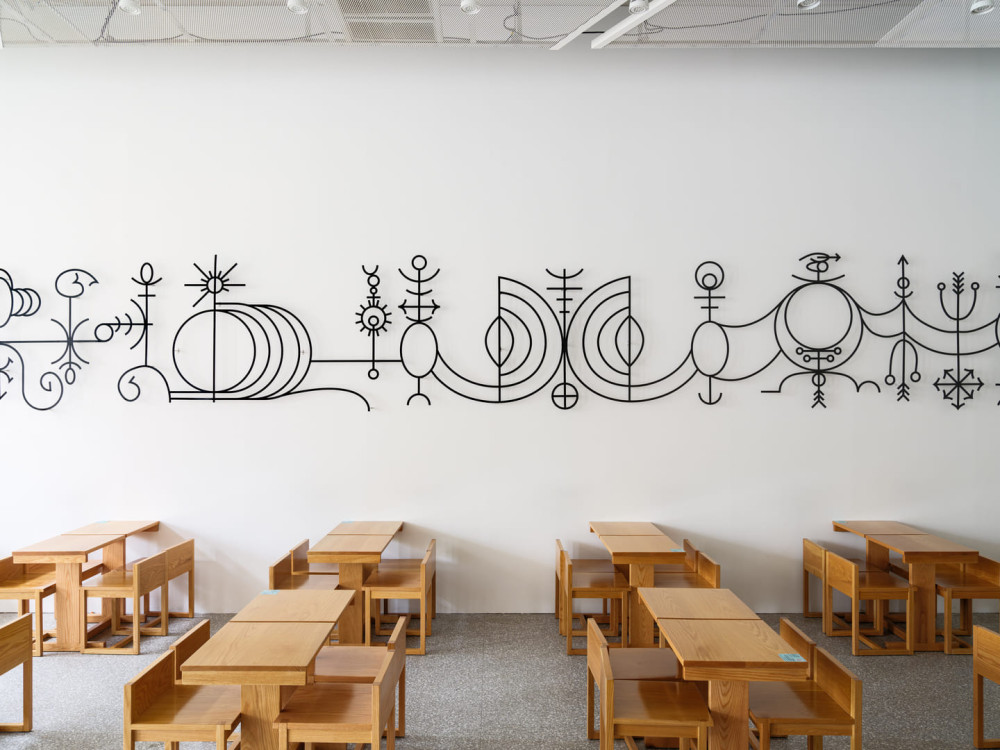

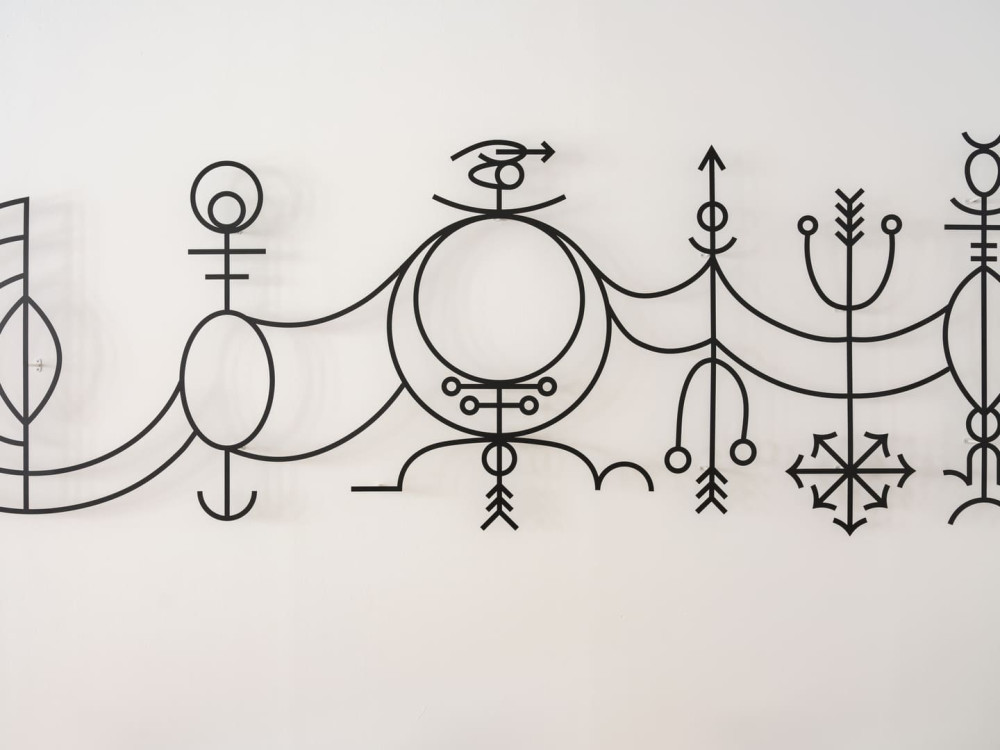

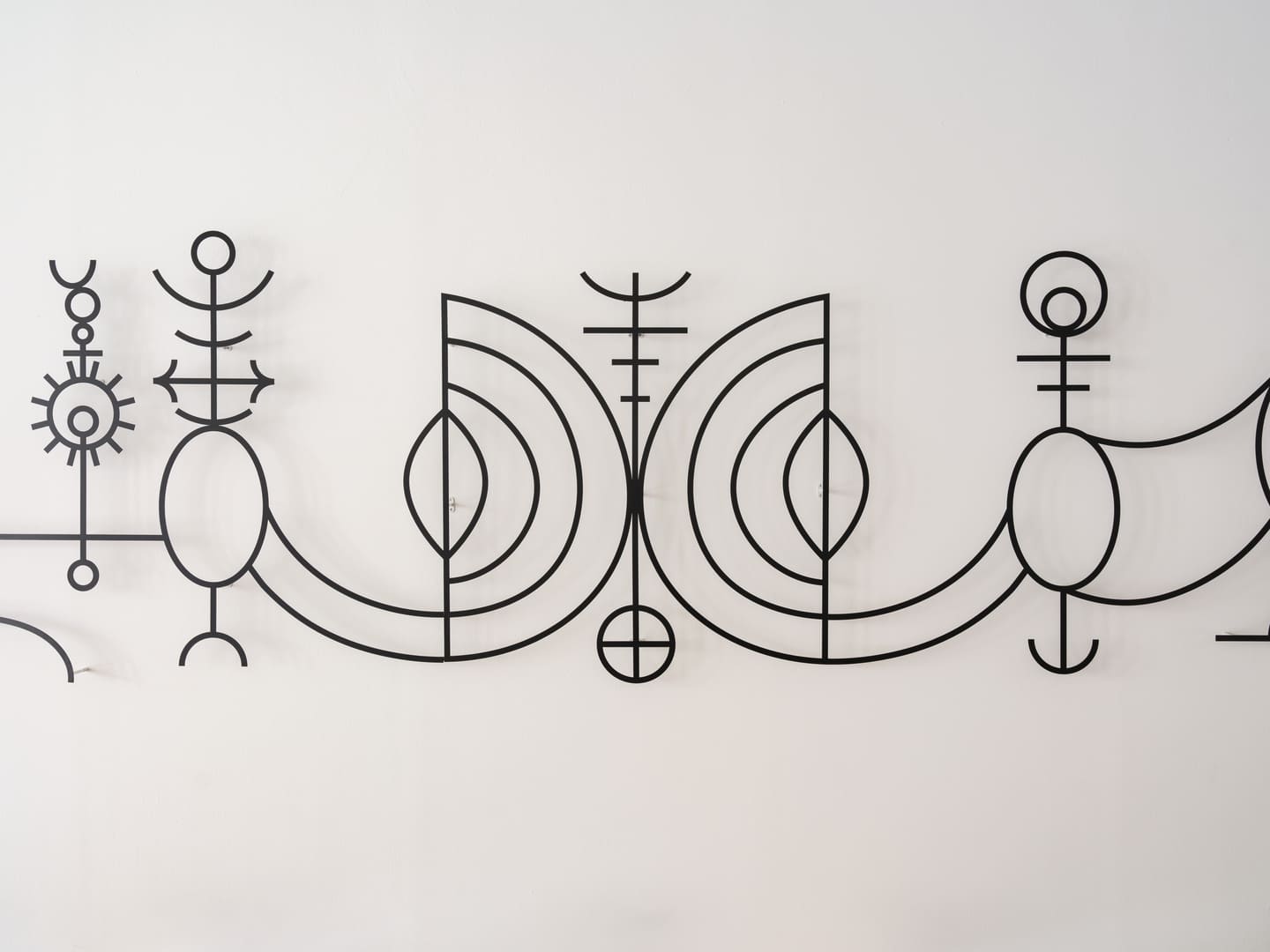

Even considering the shift in official attitudes towards Africa that followed the conclusion of the “five gray years” and Cuba’s intervention in the Angolan Civil War, it is surprising that Queneditt Morales should have been awarded the commission for a mural at the National Theater, a flagship of the government’s cultural project that opened in 1979. It is doubly surprising given that Queneditt Morales’s design for the café pays explicit homage to Abakuá, a secret religious society founded by freeborn Africans which had historically been suppressed by the Communist authorities. The mural was dismantled in the 1990s; this reconstruction is based on the handful of photographs to survive of a work that transplanted the symbols of Afro-Cuban spirituality into the heart of a secular official culture.